Large Whale Entanglement Response

Entanglement, or by-catch, is a global problem that affects many marine mammals, and can be fatal. For smaller marine mammals in Hawai‘i, like monk seals and dolphins, death is typically more immediate and due to drowning. Large whales, like humpback whales, can typically pull gear, or parts of it, off the ocean floor for months at a time and for thousands of miles, and are generally not at immediate risk of death. However, the risk and its impacts remain. Entanglement may result in starvation or drowning due to restricted movement, physical trauma, and systemic infections. It may also put whales at greater risk of other threats, like being hit by vessels.

Who Can Disentangle Whales

Whale rescue is complex and dangerous for the whale rescuers as well as the animal. Do not try to disentangle a whale yourself. Instead, learn how you can help.

Due to the risks of disentanglement and the protected status of the animals, large whale entanglement response activities involving any close approach (closer than 100 yards) to the animal are authorized and overseen by NOAA Fisheries’ National Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program (MMHSRP; permit #18786). Response to entangled whales may only be attempted by persons who are experienced, trained, knowledgeable, have proper support and equipment, and are authorized under NOAA Fisheries’ MMHSRP permit.

The Hawaiian Islands Large Whale Entanglement Response Network

Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary coordinates the community-based Hawaiian Islands Large Whale Entanglement Response Network. The network is part of the larger Pacific Islands Marine Mammal Response Network headed by NOAA Fisheries’ Pacific Islands Regional Office. The entire effort, plus associated monitoring, is overseen and authorized by NOAA Fisheries’ Marine Mammal Health and Stranding Response Program.

The network is dependent upon the commitment of many state and federal agencies, including the state of Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources, the NOAA Fisheries Pacific Islands Regional Office, the NOAA Office of Law Enforcement, and the U.S. Coast Guard, private non-governmental organizations, fishermen, researchers, and other members of the on-water community working together.

The network encompasses more than 350 members who have received various levels of training in order to support large whale response efforts statewide. Over 700 hours of training have been conducted since 2002, underscoring the importance of training and preparedness. Caches of specially-designed equipment have been established on the islands of Hawaiʻi, Maui, Oʻahu, and Kauaʻi to support entanglement response efforts.

Network Goals

The Hawaiian Islands Large Whale Entanglement Response Network attempts to free humpback whales and other marine animals with life-threatening entanglements. Even so, not every whale can be saved. The network’s main goal is to save some whales and at the same time gather valuable information that will help mitigate the issue of entanglement and its future impacts.

- Safely free some large whales, like humpback whales, from life threatening entanglements.

- Increase awareness of entanglement in order to promote stewardship.

- Reduce the response risk for any well-intentioned person(s) and authorized responders.

- Help gather valuable information that will reduce entanglement threats in the future.

Large Whale Entanglement Response Technique

Since the threat of entanglement to large whales is not typically immediate, there is time to cut the animal free. However, freeing a 45-foot, 40-ton, and typically free-swimming animal is not an easy task and can be quite dangerous for any rescue team as well as the entangled animal.

To do so safely, a boat-based technique called “kegging” is generally used to make the animal more approachable. Historically, whalers attached barrels or kegs to whales by harpooning them. The extra drag and buoyancy of the kegs would tire the whale out and keep it at the surface where it could eventually be lanced to death. For entanglement response purposes, rescuers throw grapples or use hooks on the end of poles to attach to the gear entangling the animal. Instead of barrels, the network uses large polyballs (buoy floats) for buoyancy and drag to keep the whale at the surface, slow it down and generally tire it out.

The desired result is a whale that is more approachable, allowing rescuers to safely assess the animal. Specially designed hooked knives on the end of poles are then used to cut the animal free of all entangling gear.

Disentanglement Tools

Large whale entanglement response tools are specially designed. Grapples and skiff hooks, thrown and attached to poles, help grab the animal via the entangling gear. Large air-filled polyballs act as modern-day kegging barrels. Rather than the wooden skiffs of 1800’s whaling, inflatable boats are generally used for close-approach response work. Hooked knives, dull on the outside, but sharp on the inside – so they cut the entangling gear but not the whale – are attached to long carbon-fiber poles. Some of the knives remain fixed to the poles, while other can slip off, with control maintained by attached lines. Cutting grapples allow some knives to be thrown and provide an extra level of safety.

Technology

In addition to specially designed tools that help responders get hold of and cut free large entangled whales, the sanctuary and the network use transmitters and receivers to automatically and remotely track entangled whales over time. This science, called telemetry, is an important tool for whale response. The Hawaiian Islands Large Whale Entanglement Response Network uses telemetry to track and re-locate entangled whales that cannot be disentangled during the initial response due to limited resources, and/or condition restraints.

The network uses Argos (satellite), GPS-based, and VHF radio transmitters to track entangled whales. Transmitters are secured on a telemetry buoy, which is attached to the entangling gear trailing behind the animal. Transmitters, receivers, antennas, and telemetry buoys, like the entanglement response tools, are strategically placed throughout the state with trained personnel. Telemetry increases the safety of entanglement response operations, and may assist in their overall success.

The sanctuary and its partners also use small unmanned aircraft systems (sUAS), or drones, to provide remote aerial assessment of the animal and its entanglement, as well as to document the response operations. UAS platforms increase the operational safety of response efforts by providing remote risk assessment that reduces any impact to the animal, and at the same time, minimizes risk to the authorized responders by reducing the time responders are near the animal. Like any tool, it must be used appropriately and meet the requirements outlined by NOAA, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), permit office, and others.

The sanctuary also uses heads-up-display glasses connected to a camera near the end of the pole to view the knife remotely. Like a surgeon’s tools, the real-time streaming display allows precision cuts, and increases safety by maintaining distance between the animal and responder.

In addition, the sanctuary is pursuing the use of suction-cup acoustic tags on entangled whales. These tags are placed on the animal using suction cups, while the animal is still entangled or soon after being freed. Tags may provide information on the animal’s communications, movement patterns, and energetics both during and after being freed.

Accomplishments

Since 2002, the sanctuary and the Hawaiian Islands Large Whale Entanglement Response Network have received more than 400 reports of large whales entangled in gear. Over 200 of these reports were confirmed, representing more than 140 different animals. All but a few have been humpback whales.

The network does not, and cannot, respond to every report of an entangled whale. Past responses and thorough vetting of initial entanglement reports have shown that approximately half of the reports in Hawaiʻi have been misreported or cannot be confirmed. Examples of misreports include: white-flippered humpback whales interpreted as carrying gear; animals near gear, but not entangled; reflections off the wet backs of animals interpreted as buoys; calves being interpreted as gear; and surface behaviors, like breaching, being interpreted as animals trying to throw an entanglement.

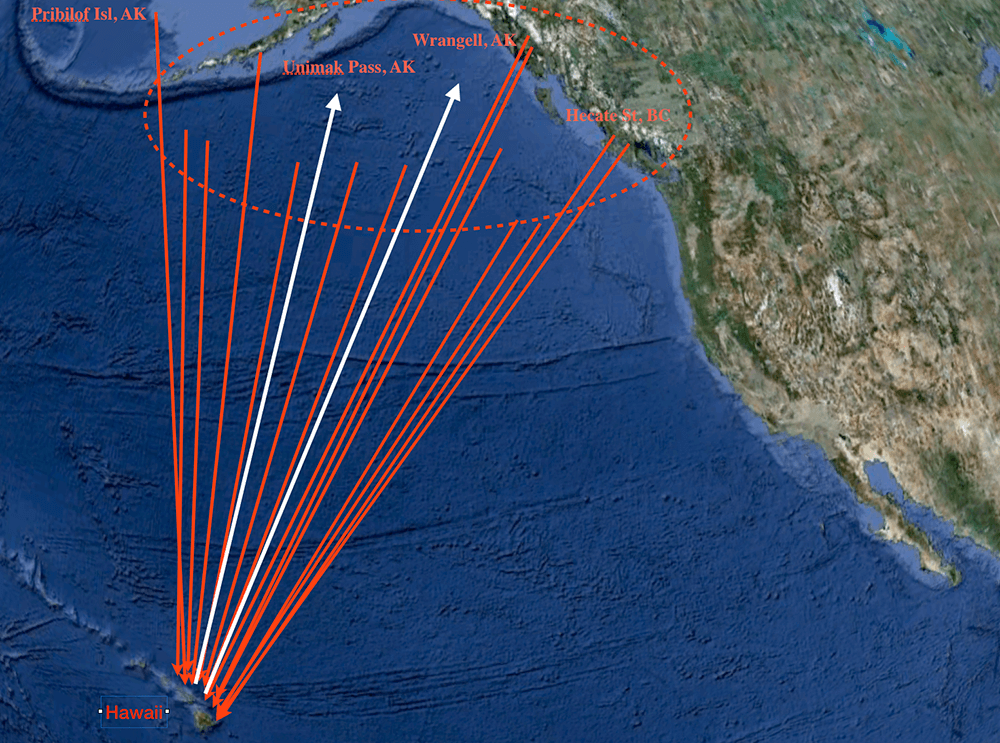

The network has mounted more than 180 on-water or in-air responses, including efforts to tag, disentangle, or assess whales. In those cases when an on-water response should and could be mounted, the network has nearly a 40% success rate freeing entangled large whales of all or significant amounts of gear. Many reports come in too late in the day, represent animals too far offshore, and/or are in conditions that are not conducive (for example, the seas are too rough) for mounting safe rescue efforts. However, the biggest contributor to an unsuccessful response is simply not re-locating the animal. If there is no standby vessel, then an entangled whale ends up being a rather large needle in an even larger haystack – the North Pacific Ocean.

Since 2002, the network has removed and/or recovered gear off more than 30 humpback whales, representing more than 12,000 feet of measurable gear. These disentanglements significantly increase the animals’ chances of survival.

Animals have been confirmed entangled in local fishing gear (traps, longline, and monofilament), mooring gear, marine debris, fish aggregating devices, and actively-fished gear set as far away as Alaska. To date, more than 20 humpback whales reported entangled in Hawaiʻi have been confirmed as carrying gear from Alaska or British Columbia, Canada. The greatest known straight-line distance (accounting for obstacles) a whale has carried gear is over 2,450 nm (between Wrangell, Alaska, and Maui). Fixed-gear – gear that is set and left, whether fishing gear, aquaculture gear, scientific equipment, or other anchored gear – was the most prevalent gear type documented on entangled large whales reported around the main Hawaiian Islands.

Entanglement Mitigation

Through our large whale entanglement response efforts and associated monitoring and research, the sanctuary and our partners strive to gain valuable information that will help reduce entanglement threat in the future for many more humpback whales and other marine animals. For instance, the network’s efforts may inform the use of more “whale-safe” fishing gear, or encourage pursuit of the appropriate use of acoustic alerts. Reducing the rate and impact of entanglements is the ultimate goal.

To date, the sanctuary has identified more than 60 sets of entangling gear.